ARTHUR D. LITTLE AND PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

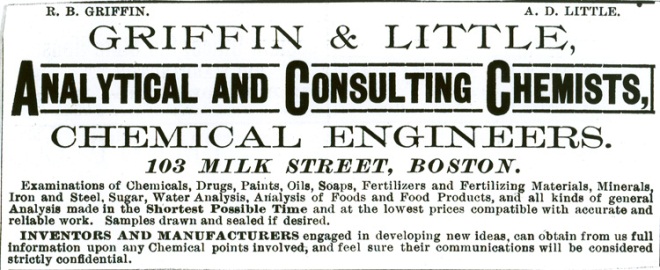

Roger Burrill Griffin partnered with Arthur D. Little in 1886 to form Griffin & Little, Chemical Engineers. Griffin was the Analytical Chemist working hard in the laboratory.

Arthur Little was described –at times– as the salesman, but others (including me) see him more as a philosopher, looking to the future and combining a zeal for research and development with a concern for the environment. (Although Roger Griffin had to be a bit of a dreamer too. Look at his choice of a legendary creature that was part eagle, part lion, part serpent or scorpion, as a logo.

I have often wondered about the story behind the choice of that logo. Although, I understand that it was the Griffin Family Coat of Arms. But then again the flying part of the acorn was a tad whimsical and subtle.)

I have often wondered about the story behind the choice of that logo. Although, I understand that it was the Griffin Family Coat of Arms. But then again the flying part of the acorn was a tad whimsical and subtle.)

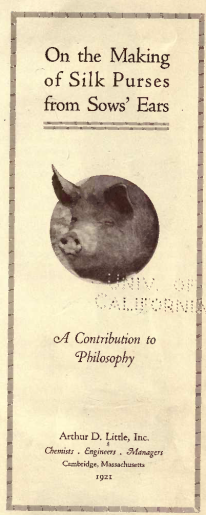

There was a sense of fun that they applied to their writing, that must have permeated their work. Just think about making silk purses:

“ Undoubtedly sows’ ears lose somewhat of their individuality when handled in one-hundred pound lots, —more so, for instance, than persons,—but we like to think that the particular portion of glue which constitutes silk from which we made the purse was derived from the ear of a particularly estimable sow called “Sukie” back on the farm.”

Little and Griffin made chemistry and chemical engineering fun. And I do not know a better way to promote innovative product and process development. I believe a key ingredient to the success of Arthur D. Little, Inc. developing products and processes is –fun……

Hank Buccigross’ Memories of ADL

Hank, a chemical engineer, joined Arthur D. Little in 1960. He stayed for 36+ years as a full time employee and an additional 6 years–until “the end!”–as a consultant. His ADL home was Technology and Product Development. Those 36 years add up to 22,075,200.00 minutes–that is a lot of minutes, but Hank says damn few of those minutes were boring. He prefers not to dwell on assignments but rather to recall memories of the people, and the fun he had especially during the first 20 years or so.

Hank’s best memories of his early days at ADL are focused on the camaraderie among the employees. The office desks were in the laboratories, the billable work week was 37 1/2 hours. (General Gavin actually eliminated the 37 1/2 hour work week.) Vacation allotment was two weeks after the first full year of employment. Lunches were one hour long and coffee breaks were where friends were made while work was being discussed. In preparation for an open house in the R&D Division, everyone pitched in for a lab cleanup ending with pizza and beer. There were Christmas (and many other) parties, company picnics, a real softball team, and broom hockey games. [One memorable party named the GASP [Grasshoppers and Ants Survival Party (I think by John Rafferty)] was a Spring event.]

Every year the employees would plan something fun for the Christmas party-a skit or playette! Jim Birkett, of course, was a key player in these skits, as was Hank Survilas., the photographer. (I recall some of the remnants of those skits–particularly the one where John Magee gifted the ADL “limousine” to Jim Birkett. The illustrious limo was two-tone gray Checker Marathon, that was fairly ugly. Jim kept it with its ADL-1 Maine plates until it fell apart. But more about that in a later article.)

The skit (made into a movie) that Hank particularly recalled was about the “Ghost of ADL”. It concerned the return of the ADL Acorn to the campus. According to Jim Birkett, the star was a cute little secretary who was all but invisible in her giant acorn costume. All you could really see of her were her skinny little arms and legs poking out. Lots of cameo appearances by staff and administration. The ghost finally died by eating a tainted peanut in Food & Flavor. Very dramatic death scene, convulsions, quite operatic. We’ve been unable to find the movies–does anyone have any ideas?

The company picnics could be rancorous–Hank told me one story about a picnic in southern New Hampshire, where Fred Iannazzi, Sr. tackled him as he walked into the picnic area.

Ray Stevens, the company President through most of 1960, held an indoctrination program once a month at the Homestead Restaurant. Hank quoted Ray Stevens saying (in effect), “Each one of you must give our clients the best possible work for the least amount of money. Let me worry about the company bottom line.” ADL’s best years were the ones where the client was our only boss and central to our day to day activities.

Hank worked at Acorn Park in Building 15, which was first occupied in 1953. The complex was proud of its Yankee origins where being prudent was the ultimate virtue. Many of the building partitions were constructed from cinder blocks–that were easily disassembled to provide different types of space depending on a particular project’s needs. [Later steel studs and dry wall replaced the block construction.] The original entrance to Acorn Park was at the corner of Building 15. Huge snapping turtles resided in the nearby Alewife Brook. Flooding was not uncommon; the first flood or floods occurred in the 50s but Hank remembers one in 1962; many documents were lost–but a carp was found in a lift. In keeping with the flooding, Acorn Park had a fire brigade for several years led by Walther Colburn.

Hank got to know a number of memorable people. One of the smartest men Hank ever met was Bernie Vonnegut, an atmospheric scientist and chemical engineer (and brother of Kurt Vonnegut). Bernie Vonnegut could explain complex physical phenomena in a few simple sentences. Dr. Vonnegut worked at Arthur D. Little from 1952 to 1967, where he studied, among other things, the suspension of a water droplet. Dr. Vonnegut discovered that silver iodide could be used to seed clouds and in 1997 he was awarded the Nobel Prize, for his paper “Chicken Plucking as A Measure of Tornado Wind Speed”.

Hank also knew three of the Koch brothers (Charlie, Dave, Billy), among the wealthiest men in the U.S.A. After graduating from MIT the three brothers worked at ADL to gain work experience. For several years Hank shared an office with Dave before he joined the family business, Koch Industries, in 1970. He noted that Dave (an MIT chemical engineer) was a good engineer, a good man and a fine human being. David Koch is a low-key philanthropist who has done much good in the world through his patronization of the sciences, cancer research, food allergies, the Smithsonian and the Museum of Natural History. Hank also crossed paths with General Gavin–Hank always wanted to salute him (likely resulting from his time in the military). He felt that saying “Good Morning Sir” just wasn’t adequate.

Another wise ADLer was Ray Hainer, a Chemist. Ray Hainer was a friend and colleague of ADLer-Don Schon (a Harvard philosopher), who wrote “Displacement of Concepts”. This book interprets the history of the ideas of all time. Ray influenced that seminal work with his ideas focused on R&D as rationale, pragmatic, multicultural, and existentialist. Hank said that Ray just made you think–for example Hank recalls having a conversation with Ray (that began in the men’s room) about the philosophy of a safer cigarette and how do you make a safer cigarette? (It is no wonder that the talk over lunch or coffee was hours long.) Hank also worked with Roger Doggett and Laurence Hervey. Neither of these men had the benefit of up-to-date chemical/engineering training. But they had a superb understanding of fundamentals and were excellent PHENOMONOLIGISTS. [aka. Detectives?] That is, they saw more than most from the results of an experiment and instinctively knew what the next experiment should be. They were a great help to the young engineers. [Ray Hainer’s booklet- “Rationalism, Pragmatism and Existentialism” -explains “phenomenology” as it pertains to R&D, but we have been unable to find that booklet.]

Hank saw repeated reorganizations during his ADL years. In the early 60s, there were 6 divisions: Research and Development, Engineering, Life Sciences, Energy and Materials, Advanced Materials, and Management Services. In the early 70s-the technical divisions were reduced to three: Engineering, Life Sciences, and Research and Development; while, management consulting expanded to three: Management Services, Management Counseling, and Industrial and Regional Economics. Also, an International Division was added. The layers of organization grew through the 70s and 80s with the addition of unit managers, directors, and practice managers. By 1980, there were thirty operating sections with an ever increasing number of vice presidents. Then seven directorates were grouped into three major businesses. This continued through the 80s and 90s and into the new millennium. There was also the going public and going private fiasco. Hank noted that it looked as though the thinking was that a change in structure would increase revenue or, more cynically, a way to retain corporate power in the hands of a few. One piece of the organization that Hank greatly respected was the Report Center and Editor Lou Visco. Reports were ADL’s final product-respect for Lou’s efforts makes a great deal of sense.

For the most part Hank’s projects concerned materials. He was an expert witness for numerous litigation cases for a variety of products. Although he was not involved in it, Hank recalls one memorable assignment at ADL was the “weed assignment”, led by Phil Levins. The weed was marijuana. (I still remember emptying an old Bldg 15 refrigerator of deuterated THC.)

One of Hank’s associates at ADL told him that working at ADL was a trial by fire—if you survived you were meant to be there. I suspect Hank lasted 22,075,200.00 minutes at ADL, because of the fun, camaraderie and the never ending stimulation of very smart people.

25 year club inductees – 1986 (entering class of 1960)