Food and Flavor at Arthur D. Little, Inc.

The history of food at Arthur D. Little began quite early. Roger Griffin and Arthur Little frequently analyzed a variety of foods, including chickens, milk, and sugars in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Starting in the 1920s, Ernest Crocker started to determine a more objective way to classify odors. From that time, ADL scientists continued to work on odor classification and ultimately a flavor profile. In 1958, Dr. Jean Caul, with Stan Cairncross and Loren Sjöström, documented the Flavor Profile Method, along with various modifications, in the journal Perfumery and Essential Oil Record. The Flavor Profile was and is used to design and/or improve a variety of products-food, wine, liquor, tobacco, cosmetics, perfumes, kitty litter, pharmaceuticals, and environmental odors. In the 1950s, Food and Flavor was actually a part of the Life Sciences Section under then ADL Vice President Charlie Kensler. The products that were worked on over the years by Arthur D. Little, Inc. are extensive, ranging from beer and cat food to mattresses and refrigerators. The work might have been to enhance something good or find something stinky.

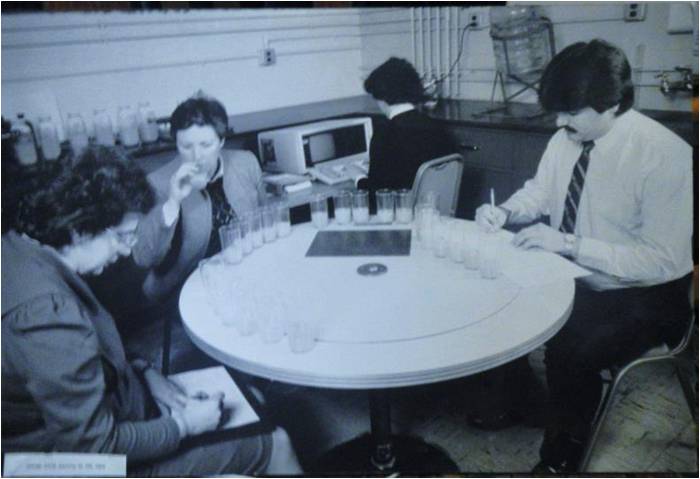

The Flavor Profile method uses a trained panel of 4 to 6 members, who individually evaluate products and then discuss the product together to determine a consensus profile. The profile describes flavor as 5 major components: character notes or attributes, intensities of those attributes (on a numerical scale that ranges to 0 to 3 with half step increments), the order of appearance of the of those attributes, aftertaste, and amplitude (or overall impression). The character notes can be the basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter, or aromatics such as chocolate, vanilla, eggy, rubbery, cabbage-like, musty.

Ginny Ferguson, Pat Keene, Mary Ann Flynn and Roy DesRochers Tasting Orange Juice

Some of ADL’s flavor scientists were infamous. Ernest Crocker was nick named the man with the million dollar nose. Of note, is the fact that the tongue registers only four basic tastes, while the nose can differentiate thousands of odors and provides most flavor sensations. Ernest Crocker claimed that there are 10,000 distinguishable odors. (This was a ball park number that has little basis in reality. But it is a number that is widely referenced.)

David Kendall and Loren (Johnny) Sjöström actually helped to diagnose a comatose child who had a rare metabolic disorder. A call came into ADL from Massachusetts General Hospital. Staff at MGH knew that ADL was doing work on odors and hoped that if the odor could be identified so they could treat the child. David and Johnny recognized and named the odor. David, as a chemist, was able to provide the correct chemical nomenclature. The doctors were ultimately able to understand that the odor was due to a missing amino acid resulting in improper metabolism of certain foods. (The child recovered and was put on a restricted diet.)

Memorial Drive and Acorn Park Buildings and Facilities

The Memorial Drive facilities ultimately encompassed three different buildings, including the original building that Arthur Little built in 1930 at 30 Memorial Drive. Another building was next door at 38 Memorial Drive, while the third faced Kendall Square on Main Street. The three facilities had chemical laboratories, animal facilities, offices, and all the infrastructure required to support those facilities.

30 Memorial Drive. Photo courtesy of MIT Archives

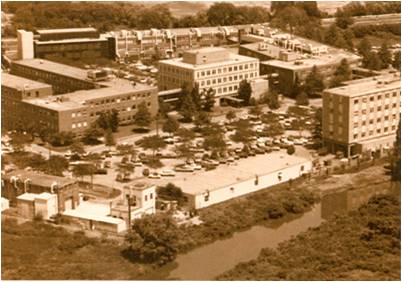

ADL opened a forty acre site for their Acorn Park laboratories and offices in November 1953. It was a rambling complex, with 6 buildings, numbered 15, 25, 35, 20, and 32 and one more simply called the Pilot Plant. The facilities included many laboratories and offices. There was also a library, conference rooms, a printing center, a credit union, travel department, mail room, medical center. Acorn Park had some first class shops for carpentry, machinery, plumbing, electricity, and photography. It was complex, and located on filled marsh land, and filled with sometimes cranky consultants, scientists, and engineers.

Acorn Park. Photo courtesy of MIT Archives

Stories from Bob and Ginny Ferguson

Bob and Ginny met at ADL. They were active participants in the infamous Silk Purse Players. Ginny was a chorus line dancer, while Bob wore a tutu with grapefruits (use your imagination). The last 2 years of the Silk Purse Players were based on a cabaret theme, before that time there were real plays. The Silk Purse Players provided their audience with a “romantic” and musical look at the world in the 60s and 70s. There was always a party after the plays and that’s where Ginny thought Bob looked good in a tutu. They met in late 1973 and married in 1975; they are likely the longest lasting ADL couple still alive today. Bob recalled that he met Ginny before 1973—an encounter with a very angry Ginny. Apparently, a pipe broke in Building 15 and the resulting stream of water landed on Ginny’s desk and destroyed photos of her nephews. Bob recalled telling his colleagues that he pitied the poor guy getting that gal (it was actually a different word). Ha! Never think that an ADL consultant (particularly a woman) doesn’t have many sides.

Ginny and Bob are looking at their 38th wedding anniversary. Together they have faced Bob’s lung cancer and Ginny’s breast cancer—and together they retired from ADL and continue a solid partnership and very happy marriage.

Ginny started her ADL career in the Food and Flavor Section in 1966. Most of the thirty years was spent training people in the Flavor Profile Method. She retired in 1996, but continued with ADL as a consultant. Currently her nose and tongue are on call to Jeff Worthington, another former ADLer. Jeff started a company named Synopsis (the name is derived from “sensory optimization systems”. Jeff’s company works on developing palatable pharmaceuticals.)

Dunkin Donuts was one of ADL’s clients. At one point the company considered adding pies to their donut selections. That required a trip to California. On her first business trip, Ginny and two male colleagues went from pie shop to pie shop tasting the product, deciding that Marie Callender’s had the best pies. To learn more about the ingredients, there was a requirement to go dumpster diving. Ginny’s colleagues won that particular prize. Dunkin Donuts didn’t add pies to their donut offerings.

The ‘70s saw a recession—and that recession hit ADLers as hard as anyone else. Billability was always the key to survival at ADL, so Ginny went to Life Sciences on Memorial Drive. There she had the opportunity to work with Sam Battista, a particularly colorful ADLer. At the Life Sciences section, research into tobacco was one of the Drive’s project areas. Research included studies into the effects of smoking cigarettes, alternatives to tobacco, flavor enhancement, and metabolic studies. One of the ways effects were studied was “smoking chickens”. The method used a cylinder that delivered puffs of cigarette smoke to hooded chickens. A rather bizarre looking set up, but an established method of study. Part of the study included counting cilia in the chickens’ trachea. (Cilia look like fine hairs lining the trachea (or throat) that sweep away small particulates, like dust or pollen.) Ginny got to count those cilia and thus maintained her billability. Back at the food and flavor section, Ginny worked on a project for an English cigarette company. The project was to develop a cigarette that was humectified (or cured) and flavored per U.S. tastes, rather than U.K. tastes. Ginny was and is a non-smoker; so her challenge when tasting cigarettes was learning how to exhale cigarette smoke through the nose.

Bob started his career at ADL at Memorial Drive in 1965. He started with cleaning the animal cages in the Life Sciences section and moved on to Maintenance, Plumbing and ultimately was the Supervisor in charge of the myriad of shops at Acorn Park. He retired in 1998.

Bob recalled one time when the ADL “higher ups” were having a meeting at the Drive, however, the barking dogs were a distraction. So the powers that be demanded that the dogs be silenced. So Bob was faced with the unenviable job of debarking the dogs (the dogs recovered and started barking again after the meeting). Another Life Sciences project was the study of a spray foam as a contraceptive—sheep were used for that study. The foam didn’t work and many little lambs resulted.

Monkeys were housed at the Drive. The monkeys were always a tad difficult to handle. So picture Bob and cohorts racing after an escaped monkey through Kendall Square. They didn’t catch him. Instead the monkey joined a business meeting at Carter’s Ink, probably looking to help ADL with marketing and sales. The monkey was returned to Memorial Drive, however, his tail had mysteriously disappeared. I’m not sure that Carter’s Ink ever became one of ADL’s clients.

In an Acorn Park incident, the drains behind the green door (a laboratory for ultra-confidential work) were blown up. It was always suspected that Sid Meyers was the culprit—but Bob was the cure.

Bob had a major job during the building of the Levins Laboratory-a lab established to study chemical warfare agents, but used for pesticides when the public decided such a facility was unwanted in Cambridge. The laboratory was totally sealed off from the environment.

During the snow storm of ’78, the boiler at Acorn Park failed. Bob was called in the fix it. He still remembers the strangeness of being the only vehicle on Route 2. As a result of the storm, all the roads were closed to non-essential personnel.

Ginny and Bob shared many adventures, one in Italy in 1989. Ginny and her ADL colleague, Mary Ann Flynn, had been working at Barilla Pasta. After completing their field work; Bob joined them for a bit of an Italian holiday. There is a luxurious and exclusive hotel—Hotel Cipriani –in Venice. So exclusive that the entrance to the hotel is blocked by a locked gate. Only hotel guests may enter on private hotel boats. But Ginny was not to be deterred and she found the back way into the hotel, using a service entrance and a public ferry boat. Armed with Gucci bags, they sauntered into the bar and enjoyed some very expensive drinks. Getting out was an equal challenge; first where was that back entrance located? According to their map, there was a church in the back of the hotel. At the hotel front desk, they requested directions to the church and made their escape, none to the wiser.

In yet another adventure, they volunteered for an experiment in the Building 20 high bay, where a tank the size of a telephone booth, as well as a full sized swimming pool was installed and filled with water in the late 60s/early 70s. (Ginny and Bob had not really met at this time. ) Dr. Thomas Davis[1] was a Medical Research consultant in the Life Sciences section. He was conducting pool experiments to develop a better life jacket, specifically one that would prevent a person’s head from entering the water when they are unconscious (prevent drowning). Bob and Ginny were lowered into a tank about the size of a telephone booth; that experiment was conducted to determine body fat. For the next step, they were fit with a prototype of a life preserver, attached to a rope harness, and submerged in water. Bob didn’t last very long, but Ginny did last. Bob was hauled out of the tank when researchers were convinced that he was drowning.

The Fergusons regularly catch up with former ADLers, including going on cruises to the Caribbean, the Panama Canal, Alaska, Europe, and Canada. The have traveled with ADLers-Connie Martin, Gus Skamarycz, Ken Howington and their wives. Their last big cruise was in 2007, they sailed to the Mediterranean with the Howingtons and Martins. Proof positive that ADLers simply live to travel.

[1] Dr. Thomas Davis became Sir Thomas Davis in 1981. Sir Davis, born in Rarotonga (the most populated of the Cook Islands), was a chief medical officer in 1949. He reorganized the Cooks’ Island health service to deliver better care to the widely scattered islands. He received a fellowship to Harvard School of Public Health in Boston in 1952. To get there, he decided to get there by boat with his wife and two sons. The trip took months and storms were a constant companion. Between school and a return to Rarotonga; he conducted research at Arthur D. Little from 1963 to 1971. He had a lifelong interest in improving safety in the water, which was the project that the Fergusons participated in. Sir Davis’s other research at ADL included the NASA space program and nutritional requirements in various climates. In a contentious 1978 election, Sir Davis became the Prime Minister of Cook Islands and held that position until 1987. He died in 2007 at the age of 90.

Bob and Ginny Ferguson

[1] Dr. Thomas Davis became Sir Thomas Davis in 1981. Sir Davis, born in Rarotonga (the most populated of the Cook Islands), was a chief medical officer in 1949. He reorganized the Cooks’ Island health service to deliver better care to the widely scattered islands. He received a fellowship to Harvard School of Public Health in Boston in 1952. To get there, he decided to get there by boat with his wife and two sons. The trip took months and storms were a constant companion. Between school and a return to Rarotonga; he conducted research at Arthur D. Little from 1963 to 1971. He had a lifelong interest in improving safety in the water, which was the project that the Fergusons participated in. Sir Davis’s other research at ADL included the NASA space program and nutritional requirements in various climates. In a contentious 1978 election, Sir Davis became the Prime Minister of Cook Islands and held that position until 1987. He died in 2007 at the age of 90.